October is Peasant Month. A month to cherish the continuous and surging selfless struggle of Philippine peasantry against all yoke of social injustice and inequality.

Peasants month started with Peasants Day

Originally, only Peasant Day was celebrated on October 21. In 1972, shortly after he assumed absolute power by declaring martial law, dictator and kleptocrat Philippine President Ferdinand E. Marcos issued Presidential Decree No. 2, declaring the whole country as a land reform area “in order to accelerate the implementation of reform both to stimulate agricultural development and to remove the source of rural unrest.” Yet, the decree failed to address landlessness and facilitated the reconcentration of huge amount of lands in the hands of the elite and foreign agribusiness corporations.

The Philippines is rich, but the people remain poor

Philippine economy remains overwhelmingly agrarian. It forms the basis for food and nutrition security and means of livelihood to about 75 per cent of labour force. This agrarian economy had become an appendage of the U.S. economy. The old feudal mode of production persists side by side with capitalist farming chiefly for the production of a few cash crops—sugar, hemp, and coconut and its products. Thus it can be described as semi-colonical and semifeudal in character. So why does the Philippines import rice? Export-oriented and import-dependent, the Philippines exemplifies the stark inequalities that neocolonialism entails. While wealthy landlords and urban dwellers live in luxury, Indigenous people, workers and peasants are forced to contend with extreme poverty, crime and state terror. These problems that beset the country are even worsened by liberalizing imports through the recently passed Rice Tariffication Law.

Forms of exploitation of peasants

- Exorbitant cost of land rent – Land rent uses up as much as 10 sacks of rice per hectare per harvest.

- High cost of production – Thousand of pesos are spent on farm implements and inputs per cropping season

- Usury – Interest rate of 15 to 35 % per cropping season (on a four-month period).

- Forced labor/slavery – Members of farmer’s families serve the landlords’ household for free.

- Unjust/unequal distribution of harvest – Maximum harvest of 40-100 cavans of palay. However, harvest is distributed by “tersya” or I/3 for the farmers; 75-25 in favor of the land owner. Cost of production shouldered by the farmers.

- Inhumane and deplorable conditions of work and intolerably low wages for farm and agricultural workers.

- Criminalization of agrarian cases – Filing of trumped up cases and harassment suits

- Eviction/disrespect of security of tenure – Displacement of farmers resulting from Certificates of Land Ownership Award (CLOA) cancellation, land use conversion, and land grabbing

- Extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances (60% of the victims are peasants)

No justice, no peace! Stop the Killings in the Philippines

The Philippines is the deadliest country in the world for people asserting their right to land and resources. As a site of land struggles, killings and harassment of peasants and land activists are perpetuated by the government and security forces.

Escalante massacre | September 20, 1985 | Escalante, Negros Occidental

At least 20 people were killed when government forces fired at a crowd of farmers were protesting the systematic oppression under the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Estimated to include 5,000 sugar workers, farmers, fishermen, and urban poor, the group was fired at by soldiers, policemen, and paramilitary forces when they held their line during dispersal.

Mendiola massacre | January 22, 1987 | Mendiola, Manila

Thirteen people were killed and 39 were injured when government forces fired at a group of 2,000 farmers who trooped to Malacañang. The farmers, who initially spent a week camping outside the Department of Agrarian Reform in Quezon City, wanted to have a dialogue with then-president Corazon Aquino regarding equal land distribution and decent wages. No one has been held accountable for the deaths of the farmers.

Lupao massacre | June 23, 1987 | Lupao, Nueva Ecija

Soldiers killed 17 people, including farmers, on June 23, 1987 in Lupao, Nueva Ecija. Witnesses reported 20 soldiers arriving in the village early in the morning, gathered residents and killed them “with gunfire and bayonets.” The massacre was blamed on the anti-insurgency campaign of the administration of Corazon Aquino. The soldiers responsible faced the military court but were later acquitted.

Hacienda Luisita massacre | November 16, 2004 | Luisita, Tarlac

The violence erupted during a picket by hacienda workers who condemned the earlier retrenchment of farmers. They also called out the flawed distribution option that would have given them stocks instead of the land the farmers needed. Protesters maintained that the police called in to disperse the crowd started the violence, adding that they directly fired at the group of farmers that led to the death of 7 while injuring at least 120 others.

Kidapawan protest incident | April 1, 2016 | Kidapawan, Cotabato

The farmers, estimated to reach 3,000, demanded government assistance amid the drought that widely affected their farms. Initiated in March 2016, they called for the release of calamity funds and sacks of rice. But the dispersal after their permit to rally lapsed turned violent. At least 50 people were injured while 3 were killed, including two police, when violence erupted between protesting farmers and government forces.

Sagay 9 / Hacienda Nene massacre | October 20, 2018 | Sagay, Negros Occidental

Nine sugarcane farmers, including 4 women and two minors, were resting in their makeshift shelter when at least 40 men reportedly fired at them. The Philippine National Police (PNP) is still investigating the case.

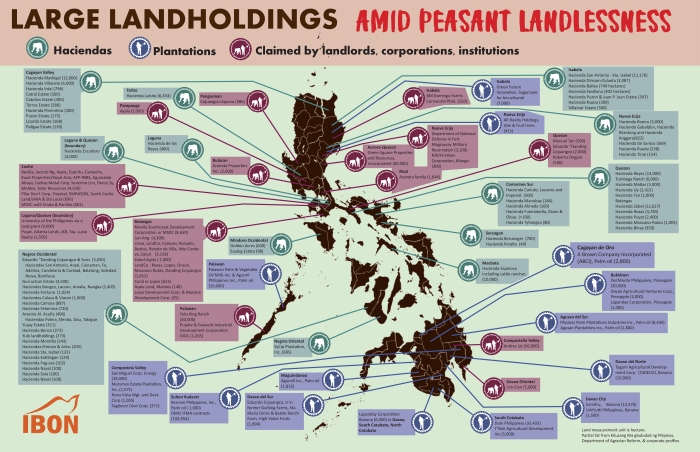

Landlessness…

Peasants remain one of the poorest sectors in the country with the highest poverty incidence. According to Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP), seven out of ten farmers remain landless. Of every 100 farmers, 21 are agricultural workers, 28 are unpaid family workers, 26 are under some form of tenancy relation and only 25 own land. Data from Landbank shows that 75 percent of amortizing agrarian reform beneficiaries were not able to pay, while the rest are still subjected to various forms of land distribution circumvention by landlords.

A centuries-old problem

Land reform has long been a contentious issue in Philippine history and Filipino peasants have always played a crucial role in the fight against colonialism. During the Spanish colonial period, more than 200 revolts against the Spanish regime were waged by the peasants themselves. The one led by Diego Silang, and later by his wife Gabriela, is a classic example. Even the Katipunan that led the 1896 Revolution was mainly composed of peasants, despite the fact that it was founded by the proletarian Andres Bonifacio. During the American period still, the forces that struggled for national liberation were predominantly peasants. The Macario Sakay revolt, the last group to fight the Americans during the Filipino-American War, was very much dependent upon the peasantry. The Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon (People’s Army Against Japan), or simply the Huk, that valiantly fought the Japanese during the Second World War and then against the Americans during the postwar period were mostly peasants from central Luzon.

And today, the New People’s Army (NPA), the fiercest group that fights against imperialism, bureaucrat capitalism and feudalism is basically peasant by composition.

What do the peasants want?

Peasant farmers and leaders want genuine agrarian reform, as the government’s agrarian reform program known as the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP), was retrogressive and merely sunk the farmers deeper into misery. CARP, signed into law by former president Corazon Aquino in 1988, was initially set for 10 years, with an aim to distribute about 7.8 million hectares of land—roughly the size of New Brunswick—to reduce inequality and help alleviate poverty. In 1998, the programme was extended by another 10 years. In 2009, Gloria Arroyo, who was president, unveiled CARPER, adding an Extension with Reforms to CARP and a deadline of 2014.

But what peasants actually wanted then was to break up land monopoly and distribute for free the agricultural lands within five years to Filipino farmers, agricultural workers, fisherfolk, and indigenous peoples and eliminate all forms of oppression and exploitation in the countryside and and guarantees that the lands would not revert back to landlords.

Cultivating the peasants movement

In 1985, the Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP), or Peasant Movement of the Philippines was established as a federation of the local peasants organizations that had gradually been formed in different areas of the country and came to play a central role in the subsequent radical peasant movement. Guided by the rich lessons of our mass campaigns and struggles, it unites with all oppressed and exploited classes, and fights for the interests and aspirations of the entire Filipino people.

KMP is a democratic and militant movement of landless peasants, small farmers, farm workers, subsistence fisherfolk, rural youth and peasant women. It has effective leadership of more than 1 million rural people with 65 provincial chapters and 15 regional chapters nationwide. It advocates and struggle for a genuine agrarian reform and national industrialization as the foundation for overall economic development; a sovereign nation free from foreign domination and control, and defends the people’s civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights. It also struggles for immediate economic relief for the peasants, launches programs and projects for livelihood and production, health, sanitation, disaster relief, and technology-development.

KMP is a founding member of Asian Peasant Coalition (APC), La Via Campesina, and the International League of Peoples Struggles (ILPS).

Some of the key dates to remember include:

October 1-16 Days of Global Action on Agroecology

October 15 International Day of Rural Women

October 16 International Food Sovereignty Day

October 17 International Day for the Elimination of Poverty

October 20 International Day of Action Against Peasant Killings

October 28 Philippine Women’s Day of Protest in the Struggle for a Just and Lasting Peace

What can you do?

Support the peasant movement and the Filipino people’s struggle for national freedom and democracy with a socialist perspective, through different means: principally to expose and oppose the so-called war against drugs, against the people in the government’s counterinsurgency program, and against the Moro people in the guise of war against terrorism. The latter war is also a very good excuse and opportunity for the U.S. government and military to intervene in the internal affairs of the country. We strongly encourage our solidarity friends to visit our country and see for themselves the struggle of the Filipino people against tyranny and oppression.

###